In this series of articles I try to answer the question "How do you make these photographs?" which I am often being asked. Because of the complexity I thought perhaps it was a good idea to write a series of articles covering the topic. There are a quite huge amount of material available on the net explaining the theories behind, so I decided to provide a step-by-step description of what I do, and at each step I will explain the reason why I do it in that way. My main focus in astrophotography is deep-sky imaging, being the field I feel to have enough experience to write about. Although Solar System or planetary imaging is another area that could be of common interest, I do not have yet enough experience in it to be the proper person to give description about.

Creating photos of deep-sky objects is a complex and lengthy process which begins with planning and preparation, and finishes with the publication of the result. In this part of the series I concentrate on the planning and preparing phase.

Planning

Planning the observing session is quite important step, because it can spare me a lot of wasted time under the dark clear sky. When I plan my next photo I consider several factors. The object to be photographed should be fit nicely in the field of view (FOV) of my equipment. Too small objects just lost in the picture, while too large ones can't fit in the frame. I could do multi panel mosaic images of more extended objects, but the low number of clear nights makes it quite difficult.

Planning the observing session is quite important step, because it can spare me a lot of wasted time under the dark clear sky. When I plan my next photo I consider several factors. The object to be photographed should be fit nicely in the field of view (FOV) of my equipment. Too small objects just lost in the picture, while too large ones can't fit in the frame. I could do multi panel mosaic images of more extended objects, but the low number of clear nights makes it quite difficult.

Currently I have only one telescope, a Sky-Watcher Quattro 10" astrograph, with two kinds of coma corrector which provide me two different FOVs, however the difference between them is not too much. Of course, if I had more telescopes with more different focal lengths I had more opportunities to choose from. In that case I had a wider range of object size I could work with, and I had the opportunity to use a smaller scope when the weather is not suitable for the bigger astrograph, for example when the seeing is poor, or the weather is windy.

Based on the brightness of the object, I determine what total integration time I plan to apply. Dimmer objects need more time, brighter ones need less. The actual time depends on a lot of factors, like the capabilities of my equipment, the quality of the sky, and my personal skills in image processing. With my equipment and with the skies I have access to I usually need several hours of total integration time for a decent photo. I have to consider this too, when I choose the object. It has to be visible at good height above the horizon (above 40-50°) for the required time. This usually means at least several nights, and bringing weather into the equation, maybe one or two months. In practice this means I don't start to shoot for an object which is already passed and visible on the western part of the sky, I rather concentrate on objects which just rise above 40-50° at the beginning of the night. Obstacles at the observing site which block parts of the sky need also to be paid attention to. I often go to a small glade in a forest to obtain images, trees around block quite a good amount of the sky, so when I take pictures of an object visible on the southern part of the sky I instal my scope on the northern part of the meadow to have better view of the southern sky. And of course the way around for northern objects.

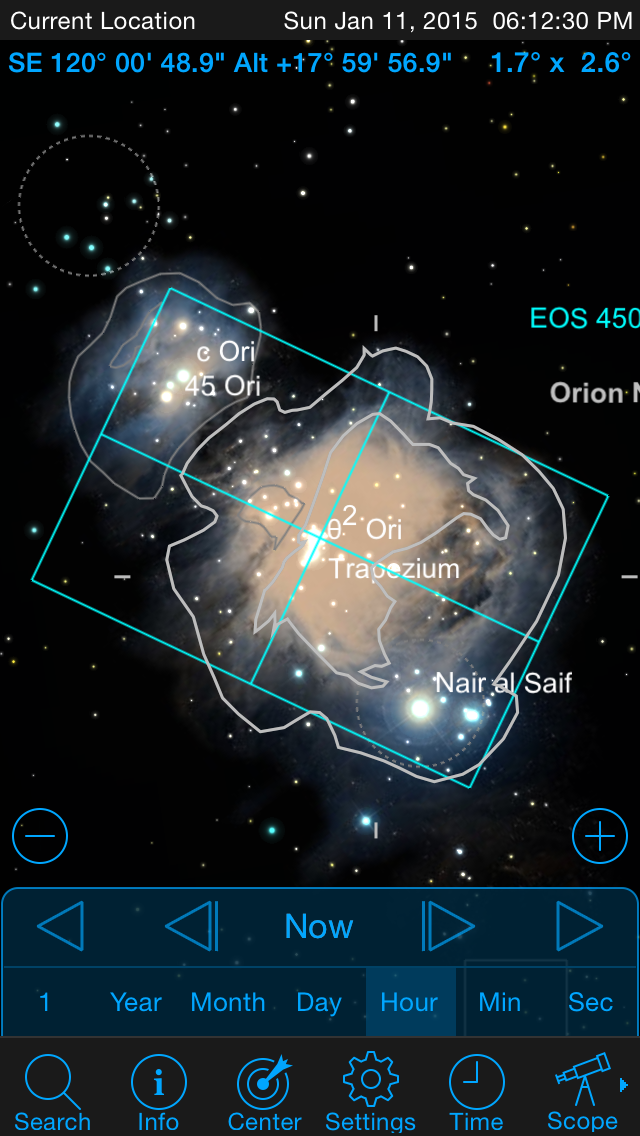

When I have the object chosen, I plan the composition. Astrophotography as its name suggests is a special field of photography, an art having its commonly accepted rules of composition. To have aesthetic result I try to comply these rules whenever it is possible. For planning the composition I use tools like FOV planner of Blackwater Skies. The installed version of Microsoft's WorldWide Telescope has such feature too, and many sky chart or planetary software has FOV simulation as well. There are even mobile apps that can be used to plan framing, which come handy (pun intended) when I happen to find myself unprepared under the sky, far from the light-polluting civilization. In the picture to the right you can see a screenshot of one of the mobile apps showing how Orion Nebula can fit in the field of my telescope and the 450D.

I pay attention to the environment of the object as well, a bright star or another galaxy having comparable brightness and size to the main object can easily destroy the balance of the picture for example. I use to print the final plan of the frame and take it with me to the field.

In the winter nights are quite long, and some objects are not at ideal position for all the night. In such case I split the night in two and I choose a second object for the second part of the night as well.

Apart of choosing the right object and planning the composition, it is also important to determine the physical phenomenon that makes the particular object interesting, and which I try to capture and introduce. I have to decide if my equipment and my skills are capable to do that. For example there are very interesting objects that are visible from my location, their apparent size is appropriate for my equipment, but they are so dim I can't collect enough data to show in an aesthetic way. Or, to show them I would need special equipment (for example infrared detector and IR-PASS filter).

Also the dynamic range needed for capturing an object is an important factor. Some objects have very bright and very dim parts at the same time. All cameras, including my Canon 450D, have limited dynamic range. In such cases I try to do HDR imaging of the object by taking light frames at different exposure times to record useful data of bright and dim parts as well.

Preparation

It is quite annoying to leave something important at home, and realize it only at the field. Once I left the SD cards at home, and realized it only after I arrived at the observing site, and installed the telescope. One and a half hours of drive to the site, and the same amount of time for assembling the scope for almost nothing. I could not take a single picture. At least I had some good time observing visually. :-) To avoid such cases I created a checklist with all the necessary items, and I go through it when I pack for observing. Depending the weather and the length of the stay I may put in some extra items like warm clothes, hot tea, sleeping bag, etc...

Because it takes several hours to fully charge the dedicated battery powering all the equipment, I put it on charger after every observing session to be prepared for the next one. After each observing session when I pack I check my equipment if any of them need cleaning or fixing, which I try to do before the next session. The equipment needs to be in proper state to be able to provide proper results.